Anastasiia Pestinova

imagen: Постер фильма К.Лопушанского ”Письма мертвого человека”/ Poster to the film of K. Lopushansky “Letters from a Dead Man”

- “Cartas de un hombre muerto” es una parábola filosófica distópica de Konstantin Lopushansky, filmada en 1986 y que ilustra la teoría del invierno nuclear. Es curioso lo clarividente que parece ser la ficción soviética: el estreno de la película coincide accidentalmente con la catástrofe de Chernóbil y, por tanto, logra un fuerte efecto en el público. El estilo del director está visiblemente inspirado en A. Tarkovsky: diálogos poéticamente escenificados, personajes arquetípicos y ese espíritu esquivo de la intelectualidad rusa, siempre orientado a una contemplación sublime de la vida cotidiana. Además, “Cartas” se publicó el mismo año que “El sacrificio”, también dedicada a la catástrofe nuclear y al replanteamiento de los ideales humanistas. A diferencia de Tarkovsky, cuya emigración no pudo sino afectar al estilo del director, volviéndolo distante y soñador, Lopushansky crea películas más oscuras y apocalípticas, sin dejar de lado el sepia y sin temer mostrar la fealdad de la vida cotidiana en un manicomio.

Tanto la utopía como la distopía representan los intentos contrarios de la mente colectiva por sondear los límites de lo posible y lo imposible, por diseñar los escenarios de evolución de la humanidad y, por supuesto, por advertir. En la cinta están representados diferentes modelos de reacción ante el colapso nuclear que se ha producido: el protagonista, un científico y premio Nobel, escribe cartas a su hijo muerto, en las que trata de encontrar una excusa y una explicación a lo que ha ocurrido con el mundo, intenta hacer cálculos y crear hipótesis, llegando finalmente a la conclusión de que todo lo ocurrido es una especie de experimento, que no puede ser la realidad. Se opone a la posición de su esposa moribunda, cuyo sufrimiento la enfada y frustra con el escapismo del marido, cree que se engaña a sí mismo. También vemos las figuras de los médicos, fríos y despiadados, que siguen estrictamente las instrucciones burocráticas y están dispuestos a condenar a muerte a los niños enfermos, porque de todos modos no sobrevivirán. El surrealismo de lo que ocurre convive sorprendentemente con el realismo pesimista, como, por ejemplo, en el siguiente diálogo.

El protagonista le dice a su amigo-doctor:

– “Realmente tengo algo en la cabeza. Posiblemente amnesia. Yo… Debo…. Centrarme en la tarea… Encontrar una hipótesis. No sé qué… qué hacer”

– “El aire de la montaña y la paz total”, responde irónicamente su amigo, y ambos estallan en una risa nerviosa pero liberadora. La ironía consiste en la referencia a la tradición popular entre la intelligentsia rusa de recreo en las aguas o en las montañas, que es finalmente imposible e inalcanzable en las condiciones del apocalipsis en curso.

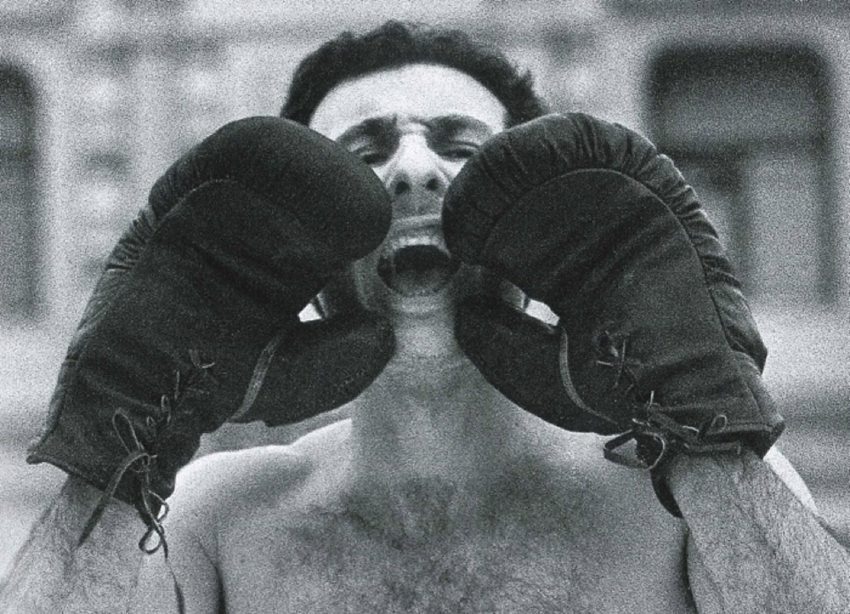

- Sergey Maximishin es un fotoperiodista ruso nacido en Odessa, ganador de múltiples concursos de fotografía, autor del libro “El último imperio. Veinte años después”, una colección de fotografías dedicada a la historia de la Rusia postsoviética. Trabajó mucho en puntos calientes: en Afganistán, Irak, Chechenia y Corea del Norte, entre otros. A Chechenia fue en el invierno de 2000, durante la segunda guerra chechena. En aquella época era muy difícil entrar en el territorio de la república, había que conocer a la gente adecuada y tener suerte. Sergey y su colega conocían a un general que les ayudó en su misión. Primero, tomaron una carretera de Mozdok a Vladikavkaz a través de Ingushetia, afortunadamente pasaron muchos puestos de bloqueo; en Vladikavkaz les esperaba un helicóptero con el general, así que al final consiguieron cruzar la frontera. La foto muestra un almuerzo de cocina de campo en el pueblo de Alkhan-Kala, al que los fotógrafos llegaron a tiempo ese día.

Sergey no se define como fotógrafo de guerra, sino como etnógrafo. En sus obras y entrevistas, plantea la cuestión de si es posible hablar de la verdad en la fotografía y dónde está la línea que separa la verdad del engaño:

“Me acuerdo de la historia de cuando los israelíes secuestraron un barco que llevaba carga para Gaza. Reuters publicó una fotografía en la que aparecían unos árabes maravillosos, gente de blanco, y entre ellos un soldado israelí con la cara torcida. Las personas de blanco parecían ángeles, y el soldado parecía un horror. El patetismo de la foto era evidente: quién es bueno y quién es malo. Pero los blogueros israelíes han descubierto que la foto estaba recortada. Y la versión completa de la foto incluía una mano con un gran cuchillo, que alcanzaba a este soldado. Al “cortar” esta mano, el fotógrafo o los editores de Reuters cambiaron el significado de esta foto al cien por cien. Una vez más, la pregunta es: ¿cuál es la verdad en la fotografía? Si la mano fue “cortada” en Photoshop o al imprimirla, es una mentira, pero ¿y si el fotógrafo simplemente se acercó un poco más y no incluyó esta mano en el encuadre intencionadamente o por accidente? ¿Sería ya verdad?”.

- “- Según un informe de Japón y Casablanca, el contraataque del ejército soviético comenzará a las seis.

– No, el contraataque comenzará a las ocho y cincuenta minutos, lo dijo Stalin.

– Coronel General, ¿usted cree a Stalin?

– Como nadie.

– ¿En qué se basa su fe? ¡Informe!

– Stalin es muy consciente de que no le creen y elige una sola opción: la verdad, porque en lugar de él nos inventamos todas las opciones imaginables e impensables, todo menos la verdad. Él dice la verdad, estando seguro de que nosotros mismos mentiremos en lugar de él – esta es su estratagema”.

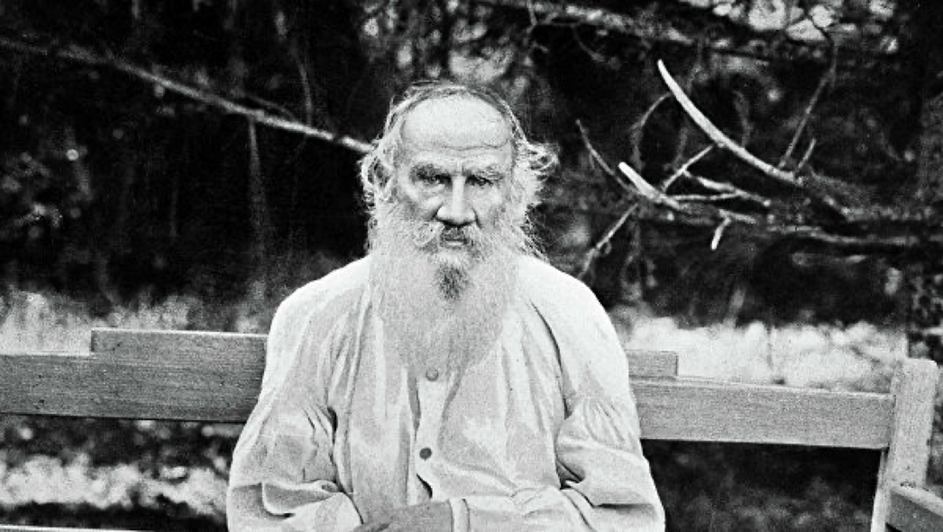

La elegía teatral de marionetas “Stalingrado” o “Canción del Volga” fue creada por el genio soviético y georgiano Revaz Gabriadze, guionista, director y artista. Entre sus famosas obras se encuentran “Mimino” y “Kin-dza-dza!”, entre otras. En una situación de caos continuo y de odio creciente entre naciones antaño amigas, me gustaría recordar los frutos de la creatividad de una persona que vivió en una época en la que coexistían juntos rusos, georgianos y otras naciones, cuando no se hablaba de descolonización de las obras de arte y las naciones estaban unidas.

La obra de marionetas se representó por primera vez en el Teatro Estatal de Marionetas de Tiflis. Está organizada como un caleidoscopio de historias de criaturas situadas en diferentes ciudades y diferentes líneas temporales, pero relacionadas entre sí: una joven, una madre-hija, un caballo de tiro Alyosha, un caballo de circo Natasha, un reparador Pilhas de Kyiv, un mariscal de campo alemán, Stalin, un general soviético Gorenko y el ángel de Alyosha. En las versiones originales de la obra, los titiriteros ensamblaban los personajes directamente en el escenario, lo que constituye un gesto muy simbólico y alquímico de recreación del universo. La narración está construida de forma no lineal, algunas frases están formuladas de forma impersonal y no encajan bien entre sí gramaticalmente, creando una sensación de collage o técnica de recorte. En algunas escenas encontramos alusiones a la historia romana: por ejemplo, el mariscal de campo aparece como la encarnación de Salvius Julius, y el caballo – un misterioso personaje que viajó con Marco Aurelio más allá de los Pirineos (mientras que en las escenas iniciales, Alyosha era un guardia que fue reclutado por los alemanes y fue condenado al conocido artículo 58 – por agitación contra la autoridad soviética). Resulta que las marionetas son controladas por unas fuerzas de otro mundo y éstas no son titiriteras, se forma una metanarrativa, una especie de trama cósmica-histórica. Una guerra atraviesa los destinos de los personajes como una franja divisoria, cortando su lienzo de vida. La música coral crea la sensación de estar en un espacio sagrado.

La imagen de un caballo utilizada por el director no fue casual, se inspiró en un fragmento de las notas de un corresponsal de guerra inglés: “Después de la batalla, cuanto más me acercaba a Stalingrado, más increíble me resultaba el paisaje circundante. Por todas partes había restos de caballos, uno, aún vivo, caminaba a duras penas sobre tres patas, arrastrando la cuarta, disparada o lisiada. Era un espectáculo desgarrador. Durante la ofensiva de las fuerzas soviéticas murieron 10.000 caballos. Todo el paisaje estaba plagado de cadáveres de caballos muertos por los tanques, las balas y los intensos bombardeos”.

- «Письма мертвого человека» – это философская притча-антиутопия Константина Лопушанского, снятая в 1986 году и иллюстрирующая теорию ядерной зимы. Любопытно то, насколько советская фантастика оказывается провидческой – выход картины случайно совпадает с чернобыльской катастрофой и потому производит сильный эффект на зрителей. В фильме ощущается влияние А. Тарковского: поэтически поставленные диалоги, архетипические персонажи и тот самый неуловимый дух русской интеллигенции, вечно устремленной к возвышенному созерцанию повседневности. Более того «Письма» выходят в том же году что и «Жертвоприношение», посвященное ядерной катастрофе и переосмыслению гуманистических идеалов. В отличие от Тарковского, эмиграция которого не могла не сказаться на режиссерском стиле, сделав его отстраненным и мечтательным, Лопушанский создает более мрачное и более апокалиптическое кино, не пренебрегая сепией и не боясь показать неприглядность русского быта.

Утопия как и антиутопия являются разнонаправленными попытками коллективного сознания прощупать границы возможного и невозможного, набросать сценарии развития человечества и, конечно же, предостеречь. В фильме представлены разные ролевые модели реагирования на произошедшую катастрофу: так, например, главный герой, ученый и лауреат нобелевской премии, пишет письма мертвому сыну, в которых пытается найти оправдание и объяснение произошедшему, параллельно проводя вычисления и строя гипотезы, в конечном счете приходя к выводу, что все, что происходит, является каким то экспериментом, такого не могло случиться на самом деле. Ему противопоставлена позиция умирающей жены, страдания которой заставляют ее с горестью относиться к эскапизму мужа, она считает, что он обманывает себя. Мы видим также фигуры врачей, которые холодные и безжалостные, строго следуют бюрократическим инструкциям и готовы приговорить к смерти больных детей, поскольку те все равно не выживут. Сюрреалистичность происходящего удивительно уживается с пессимистичным реализмом, как например в следующем диалоге.

Главный герой говорит своему другу-врачу:

– «У меня действительно что-то с головой. Возможно амнезия. Я… Надо…. Сосредоточится на задаче…Найти гипотезу. Я не знаю что…Что делать»

– «Горный воздух и полный покой», – иронично отвечает ему друг и они оба заливаются нервным, но освобождающим смехом. Ирония состоит в отсылке к популярному среди русской интеллигенции отдыху на водах или в горах, который является чем то максимально далеким и недостижимым в условиях происходящего апокалипсиса.

- Сергей Максимишин – российский фотокорреспондент, родившийся в Одессе, многократный призер фотоконкурсов, автор книги «Последняя империя. Двадцать лет спустя» – сборника фотографий, посвященного истории постсоветской России. Много работал в горячих точках: в Афганистане, Ираке, Чечне, Северной Корее и других. В Чечню поехал зимой 2000 года, в период второй чеченской войны. Попасть на территорию республики в то время было очень сложно, нужно было знать нужных людей и быть удачливым. Сергей и его коллега были знакомы с одним генералом, который помог им в их миссии. Сначала их ждала дорога от Моздока до Владикавказа через Ингушетию, у них получилось миновать множество блокпостов, а во Владикавказе их ждал вертолет с генералом, так что в итоге им удалось пересечь границу. На фотографии заснят обед полевой кухни в селе Алхан-Кала, на который успели фотографы в тот день.

Сергей не определяет себя как военного фотографа, скорее как этнографа. Во многих своих работах и интервью он задается вопросом о том, где проходит граница между правдой и обманом в мире фотоискусства:

«Мне вспоминается история, когда израильтяне захватили судно, которое шло с грузом для Газы. Reuters опубликовал фотографию, на которой такие замечательные арабы, люди в белом, а между ними израильский солдат с перекошенным лицом. Люди в белом были похожи на ангелов, а солдат похож на ужас. Пафос фотографии был очевиден: кто хороший, а кто плохой. Но израильские блогеры уличили Reuters в том, что фотография была кадрированной. А полный вариант снимка включал в себя руку с большим ножом, которая тянулась к этому солдату. «Отрезав» эту руку, фотограф или редакторы Reuters изменили смысл этой фотографии на сто процентов. Снова вопрос — что есть правда в фотографии? Если руку «отрезали» в фотошопе или при печати — это вранье, а если бы фотограф просто подошел чуть ближе и не включил эту руку в кадр намеренно или случайно? Это было бы уже правдой?»

- «– По донесению из Японии и Касабланки контратака советской армии начнётся в шесть часов.

– Нет, контратака начнется в восемь часов пятьдесят минут, так сказал Сталин.

– Генерал-полковник, вы верите Сталину?

– Как никому.

– На чем основывается ваша вера? Доложите!

– Сталин прекрасно понимает что ему не верят и выбирает один единственный вариант – правду, поскольку мы вместо него выдумываем все мыслимые и немыслимые варианты, все, кроме правды. Он говорит правду будучи уверенным что врать вместо него мы будем сами, такова его стратегема».

Спектакль-элегия «Сталинград» или «Песня о Волге» создан советским и грузинским гением Резо Габриадзе, сценаристом, режиссером, художником. В число его известных работ входят «Мимино», «Кин-дза-дза!» и другие. В ситуации происходящего хаоса и возрастания ненависти между некогда дружественными народами, хочется вспомнить плоды творчества человека, жившего в эпоху когда русские, грузинские и другие народы сосуществовали в едином поле, когда еще не шла речь о деколонизации произведений искусства, а народы были едины.

Впервые спектакль был поставлен в Тбилисском государственном театре марионеток. Он организован как калейдоскоп историй существ находящихся в разных городах и разных временных линиях, но связанных друг с другом: молодая женщина, мама муравьиха, ломовая лошадь Алеша, цирковая лошадь Наташа, киевский мастер по мелкому ремонту Пилхас, немецкий фельдмаршал, Сталин, советский генерал Горенко и ангел Алеши. В оригинале кукловоды собирали персонажей прямо на сцене. Нарратив выстроен нелинейно, некоторые фразы сформулированы безлично и не совсем грамматически состыкуются друг с другом, создавая ощущение коллажа или нарезки. Присутствуют аллюзии на римскую историю: так, фельдмаршал предстает воплощением Сальвия Юлия, а лошадь – загадочным персонажем, путешествовавшим с Марком Аврелием за Пиреней (в начальных же сценах Алеша был гвардейцем, которого завербовали немцы и которому светила известная 58-ая статья – за агитацию, содержащую призыв к свержению Советской власти). Получается, что куклами управляют некие потусторонние силы и это не кукловоды, образуется мета повествование, эдакий космически-исторический сюжет. Через судьбы персонажей разделительной полосой проходит война, взрезая жизненное полотно. Хоровая музыка создает ощущение нахождения в сакральном пространстве.

Образ лошади возник у режиссера не случайно, он был навеян отрывком из заметок одного английского военного корреспондента: «После битвы, чем ближе я подбирался к Сталинграду, тем окружающий пейзаж становился все более невероятным. Повсюду останки лошадей, одна, все еще живая, плетется на трех ногах, волоча за собой четвертую, отстреленную или искалеченную. Это было душераздирающее зрелище. Во время наступления советских сил погибло 10.000 лошадей. Весь ландшафт был усеян трупами лошадей, убитых танками, пулями и под шквальным обстрелом».

- “Letters from a Dead Man” is a philosophical dystopian parable by Konstantin Lopushansky, filmed in 1986 and illustrating the theory of nuclear winter. It is curious how prescient Soviet fiction appears to be – the release of the picture accidentally coincides with the Chernobyl catastrophe and therefore attains a strong effect on the audience. The director style is visibly inspired by A. Tarkovsky: poetically staged dialogues, archetypal characters and this elusive spirit of the Russian intelligentsia, always oriented to a sublime contemplation of everyday life. Moreover, “Letters” were published in the same year as “The Sacrifice”, also dedicated to the nuclear catastrophe and to the rethinking of humanistic ideals. Unlike Tarkovsky, whose emigration could not but affect the director’s style, making him distant and dreamy, Lopushansky creates darker and more apocalyptic films, without neglecting sepia and not being afraid to show the ugliness of everyday life in an asylum.

Utopia, as well as dystopia, represent the contrary-directional attempts of the collective mind to probe the boundaries of the possible and impossible, to design the scenarios of evolution of mankind and, of course, to warn. In the tape are represented different role models of reaction to the nuclear collapse that has occurred: the main character, a scientist and Nobel Prize winner, writes letters to his dead son, in which he tries to find an excuse and explanation for what happened with the world, he tries to make calculations and to create hypotheses, ultimately coming to the conclusion that everything that happened is some kind of experiment, this could not be the reality. He is opposed to the position of his dying wife, whose suffering makes her angry and frustrated with the escapism of the husband, she believes that he is deceiving himself. We also see the figures of doctors who are cold and ruthless, strictly following bureaucratic instructions and ready to sentence sick children to death, because they will not survive anyway. The surrealism of what is happening surprisingly coexists with pessimistic realism, as, for example, in the following dialogue.

The main character says to his friend-doctor:

– “I really have something in my head. Possibly amnesia. I… Must…. Focus on the task… Find a hypothesis. I don’t know what… what to do”

– “Mountain air and complete peace,” – replies his friend ironically, and they both burst into nervous but liberating laughter. The irony consists in reference to the popular among the Russian intelligentsia tradition of recreation on the waters or in the mountains, that is ultimately impossible and unattainable in the conditions of the ongoing apocalypse.

- Sergey Maximishin is a Russian photojournalist born in Odessa, multiple winner of photo contests, author of the book “The Last Empire. Twenty years later” – a collection of photographs dedicated to the history of post-Soviet Russia. He used to work a lot in hot spots: in Afghanistan, Iraq, Chechnya, North Korea and others. To Chechnya he went in the winter of 2000, during the second Chechen war. It was very difficult to get into the territory of the republic at that time, you needed to know the right people and to be lucky. Sergey and his colleague used to know one general who helped them with their mission. First, they took a road from Mozdok to Vladikavkaz through Ingushetia, fortunately passing a lot of block posts, in Vladikavkaz for them was waiting a helicopter with general, so in the end they managed to cross the border. The photo shows a field kitchen lunch in the village of Alkhan-Kala, to which the photographers arrived in time that day.

Sergey does not define himself as a war photographer, but rather as an ethnographer. In his works and interviews, he poses a question of whether it is possible to speak about truth in photography and where runs the line between truth and deceit:

“I am reminded of the story when the Israelis hijacked a ship that was carrying cargo for Gaza. Reuters published a photograph showing such wonderful Arabs, people in white, and between them an Israeli soldier with a twisted face. The people in white looked like angels, and the soldier looked like a horror. The pathos of the photo was obvious: who is good and who is bad. But Israeli bloggers have found out that the photo was cropped. And the full version of the picture included a hand with a large knife, which reached out to this soldier. By “cutting off” this hand, the photographer or Reuters editors changed the meaning of this photo on one hundred percent. Again, the question is – what is the truth in photography? If the hand was “cut off” in Photoshop or when printing, is this a lie, but what if the photographer just came a little closer and did not include this hand in the frame intentionally or by accident? Would that be true already?”

- « – According to a report from Japan and Casablanca, the counterattack of the Soviet army will begin at six o’clock.

– No, the counterattack will begin at eight and fifty minutes, Stalin said so.

– Colonel General, do you believe Stalin?

– Like no one else.

– What is your faith based on? Report!

– Stalin is well aware that they do not believe him and chooses one single option – the truth, because instead of him we invent all conceivable and unthinkable options, everything but the truth. He tells the truth, being sure that we ourselves will lie instead of him – this is his stratagem».

The puppet-play elegy “Stalingrad” or “Song of the Volga” was created by the Soviet and Georgian genius Revaz Gabriadze, screenwriter, director, artist. His famous works include “Mimino”, “Kin-dza-dza!” and others. In a situation of ongoing chaos and growing hatred between once friendly nations, I would like to recall the fruits of creativity of a person who lived in an era when Russian, Georgian and other nations used to coexist together, when there was no talk about decolonization of works of art and the nations were united.

The puppet play was staged for the first time at the Tbilisi State Puppet Theatre. It is organized as a kaleidoscope of stories of creatures located in different cities and different timelines, but related to each other: a young woman, a mother-ant, a draft horse Alyosha, a circus horse Natasha, a repairman Pilhas from Kyiv, a German field marshal, Stalin, a Soviet general Gorenko and the angel of Alyosha. In the original versions of play, the puppeteers assembled the characters right on the stage that is a very symbolic and alchemic gesture of recreation of universe. The narrative is built in a non-linear manner, some phrases are formulated impersonally and do not fit well with each other grammatically, creating a feeling of collage or cut-up technique. In some scenes we find allusions to Roman history: for example, the field marshal appears as the incarnation of Salvius Julius, and the horse – a mysterious character who traveled with Marcus Aurelius beyond the Pyrenees (while in the initial scenes, Alyosha was a guardsman who was recruited by the Germans and was convicted to the well-known 58th article – for agitation contra Soviet authority). It turns out that the puppets are controlled by some otherworldly forces and these are not puppeteers, a meta narrative is formed, a kind of cosmic-historical plot. A war passes through the fates of the characters as a dividing strip, cutting through their canvas of life. Choral music creates the feeling of being in a sacred space.

The director’s image of a horse was not accidental, he was inspired by an excerpt from the notes of an English war correspondent: “After the battle, the closer I got to Stalingrad, the more incredible the surrounding landscape became. Everywhere are the remains of horses, one, still alive, trudges on three legs, dragging the fourth, shot or crippled. It was a heartbreaking sight. During the offensive of the Soviet forces, 10,000 horses died. The whole landscape was littered with the corpses of horses killed by tanks, bullets and under heavy shelling».