Anastasiia Pestinova

En la ola de dudas del mundo sobre la posición del arte ruso en relación con el discurso del militarismo, vale la pena subrayar el hecho de que es muy difícil mantener una línea de demarcación entre lo poético y lo político. Si el poeta de cierta época canta una guerra, ¿significa esto que tiene que ser excluido del patrimonio cultural? Y viceversa: ¿es la retórica antibélica realmente capaz de salvar a la humanidad de conflictos y catástrofes? Más directa y abiertamente se manifiesta el sentido, más lejano es de lo poético, porque la verdad es multifacética, misteriosa y no tolera el modo de interrogación. El talento poético está correlacionado con la posición civil del autor, pero no depende completamente de ella. Los intentos de reducir uno a otro siempre corren el riesgo de colapsar en la coyuntura. Sin embargo, en el ámbito artístico ruso encontramos una rica tradición de artistas plenamente conscientes del lado horrible de la guerra, lejos de ilusiones tranquilizadoras y sin miedo a enfrentarse a lo absurdo y terrorífico que conlleva. La comprensión de la brutalidad descubierta de la guerra es la única manera de no perder el humanismo y los valores que hacen que la vida sea tan precioda. Y, por el contrario, la paranoia resulta ser la cara opuesta del autoengaño.

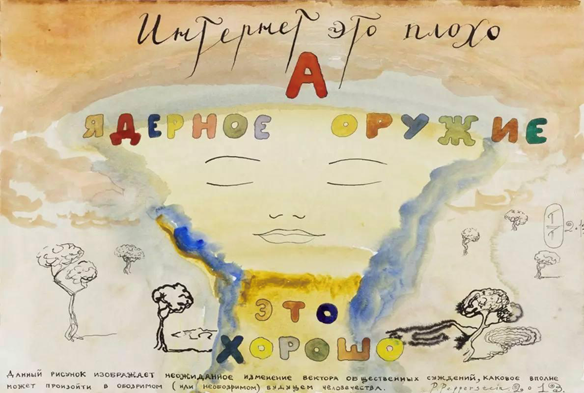

- Uno de los rostros del conceptualismo moscovita, creador de mundos esquizoides y fantásticos, Pavel Pepperstein, presentó en 2014 una serie de obras llamadas “Holy Politics”, entre las que destaca el cuadro de título provocador “Internet es malo y las armas nucleares son buenas”. 2014 es el año de la culminación de la crisis europea, cuyo carácter catastrófico y apocalíptico fue comprendido por el artista, y cuyas consecuencias sentimos todos en este momento.

Según Pepperstein, Internet y el pensamiento en red que genera no son menos, quizá incluso más peligrosos, que la televisión “zombi” -en referencia al tópico popular de las noticias falsas-. Un canal de propaganda no es muy diferente de otro, ambos forman la ilusión de comunidad y pertenencia a algo más grande que el individuo, tóxico para la conciencia. La identificación de uno mismo con uno u otro flujo de información amenaza con la inestabilidad mental y la pérdida del Yo.

La afirmación “Las armas nucleares son buenas” ilustra el totalitarismo del hecho, que tiene un efecto amortiguador en la conciencia. A lo que nos enfrentamos mirando el cuadro es a la oposición de colores suaves, delicados y aéreos con contornos finos, en contraste con el horror del mensaje principal. Esto representa la oposición de la vida y la muerte. De este modo, Pepperstein resuelve una cuestión muy importante: proteger a las personas de los envites de la realidad creando un cierto espacio para lo inexistente, una barrera y una distancia dentro de nosotros mismos que permita no identificarnos de inmediato, completa e irreflexivamente, con los puntos de vista propuestos sobre los acontecimientos que se nos ofrecen de forma asfixiante. Revelar y fijar las fuerzas y los campos que determinan el pensamiento proporcionan la oportunidad de redefinir la posición de uno en su juego, para no ser prisionero del hecho. La multidimensionalidad de la conciencia, la multiplicidad de mundos y la fantasía infantil son los antídotos del totalitarismo.

Lo que el artista propone no es un escapismo, sino el sueño y el humanismo, que son los únicos capaces de conservar la conciencia en la lucha contra la muerte.

- “Los gobiernos aseguran a las naciones que están en peligro de ser atacadas por otras naciones o por enemigos internos, y que la única forma de salvarse de este peligro reside en la obediencia servil de las naciones a los gobiernos. Esto se ve claramente durante las revoluciones y las dictaduras, y así sucede siempre y dondequiera que el poder esté en juego. Todo gobierno explica su existencia y justifica toda su violencia diciendo que si la gente no hubiera sido golpeada, habría sido peor. Tras asegurar a las naciones que están en peligro, los gobiernos las someten. Cuando las naciones se someten a los gobiernos, éstos obligan a las personas a atacar a otras. Y así, para estas naciones, se confirman las seguridades de los gobiernos sobre el peligro de ataque de otras naciones”.

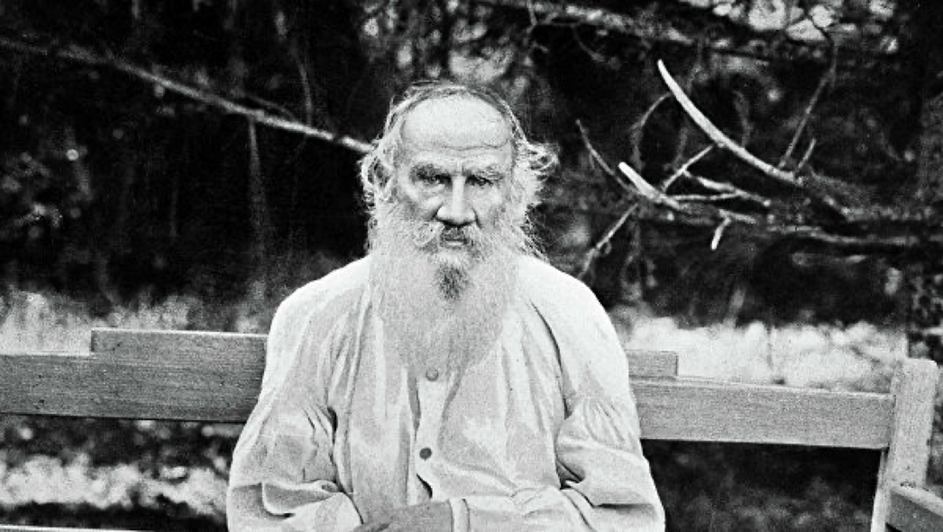

Este es un fragmento de un artículo de L.N. Tolstoi “El cristianismo y el patriotismo”, escrito en 1893, pero que no se publicó debido a la censura. En este artículo realiza un profundo análisis y crítica del fenómeno del patriotismo que se pone al servicio del poder y que lleva al pueblo a la muerte espiritual y física. Escrito tras el acuerdo de la alianza franco-rusa de 1893 como reacción a la ola de festejos que surgió en la sociedad, el artículo expresa ante todo la indignación contra la oscuridad y la ingenuidad del público, incapaz de comprender la falsedad de la alegría superficial, sino que se muestra encantado y dispuesto a celebrar todo lo que ocurre.

Psicólogo sutil tanto en el plano de la individualidad como en el de la sociedad, Tolstoi desacredita el patriotismo como principal estratagema ideológica de las dictaduras, al que se recurre para manipular la conciencia del pueblo. Tolstoi denuncia ese patriotismo que divide a las naciones y a los pueblos, que siembra la discordia entre las personas y que, bajo la apariencia de un ideal de moralidad, se convierte en una justificación de la violencia. Con la ayuda de ese patriotismo quienes realmente se benefician son los gobernantes políticos, los que en aras de sus propios intereses, obligan a mucha gente engañada, de corazón sencillo, a derramar su propia sangre y la de otros. Cuando el amor por un estado se convierte en daño a otro, el amor se convierte en fuerza destructiva, se convierte en odio.

- La película apocalíptica de culto “Ven y verás”, dirigida por Elem Klimov, es un drama bélico despiadado para el espectador, estrenado en 1985 en el cuadragésimo aniversario de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Rodada durante el periodo de la Guerra Fría ante el temor de la Tercera Guerra Mundial, la película es la encarnación de las pesadillas de la guerra y se considera casi como la película más difícil de ver. Su acción se desarrolla en 1943 en Bielorrusia, donde, como parte del “Plan General Ost” adoptado por la Alemania nazi, el ejército de la Wehrmacht lleva a cabo operaciones de castigo con el objetivo de hacer una “limpieza” total de la población civil. La trama se construye en torno a un niño llamado Flyora que, al pasar por las pruebas de la guerra, sufre cambios psicológicos irreversibles que se reflejan directamente en su rostro: el niño se convierte en anciano. La muerte de la familia, los intentos de suicidio, el peligro de ser quemado vivo, la presencia forzada en una ejecución masiva y la observación constante de escenas de violencia contra los compatriotas, son sólo algunos de los círculos infernales que el espectador atraviesa con Flyora. La película está llena de coloridos símbolos-metáforas de oposición entre la vida y la muerte: una danza bajo la lluvia y una garza que sale del bosque frente a la agonía de una vaca moribunda y las moscas que revolotean sobre los juguetes de los niños.

La selección de actores para el papel principal se llevó a cabo de una manera especial: Klimov mostraba a los aspirantes al papel una crónica de los campos de concentración y luego ofrecía té con pastel, esperando que alguien se negara. Alexey Kravchenko fue el único que se negó y por eso obtuvo el papel. Se le asignaron psicólogos y se desarrolló un programa especial de asistencia psicológica que permitió al actor mantener su salud mental durante el proceso de rodaje.

Hay un proverbio ruso que dice: “piensa en el pasado y pierde un ojo; olvida el pasado y pierde los dos ojos”. No se trata de un castigo por el olvido, sino de que no hay nada más peligroso que el olvido. Klimov prefirió conservar al menos un ojo y dejar para siempre una marca en la memoria del inconsciente colectivo. Quien haya visto esta película, se vacuna de cualquier intento de romantizar el curso de las hostilidades y se afirma en la comprensión de que en una guerra sólo se puede perder.

На волне мировых сомнений насчет позиции русского искусства по отношению к милитаристскому дискурсу важно подчеркнуть сложность проведения линии демаркации между поэтическим и политическим. Если поэт в ту или иную эпоху воспевает войну – означает ли это что его или ее произведения необходимо исключать из культурного наследия? И наоборот – насколько действительно предохраняет и спасает антивоенное искусство от конфликтов и катастроф? Чем более прямо и открыто манифестируется тот или иной смысл, тем дальше он от поэтического, потому что правда многогранна, таинственна и не терпит режима допроса. Поэтический талант находится в связке с гражданской позицией автора, но не целиком от нее зависит. Попытки однозначно свести одно к другому всегда будут вырождаться в конъюнктуру. В русском художественном пространстве существует традиция искусства, глубоко осознающая ужасающую сторону войны. Далекая от успокаивающих иллюзий, она не боялась посмотреть в лицо абсурду и террору. Понимание жестокости военных действий – это единственный способ не утратить гуманность и человечность, которые делают жизнь главной ценностью. И наоборот паранойя оказывается обратной стороной самообмана.

- Представитель московского концептуализма, создатель шизоидных и фантазматических миров Павел Пепперштейн представил в 2014 году серию работ под названием «Святая политика», в которой особой актуальностью выделяется картина с провокационным названием «Интернет это плохо, а ядерное оружие это хорошо». 2014 год – год кульминации европейского кризиса, катастрофичность и апокалиптичность которого была прочувствована художником и последствия которого все мы, жители земли, ощущаем в настоящий момент.

По представлениям Пепперштейна, интернет и сетевое мышление, которое он порождает, ничуть не уступают, а возможно даже обладают более негативным эффектом по сравнению с «зомбирующим» телевидением – чему резонирует ставшая популярной тема фейковых новостей. Один канал пропаганды мало чем отличается от другого, оба формируют иллюзию общности и сопричастности, токсичные для сознания. Идентифицирование себя с теми или иными информационными потоками грозит психической нестабильностью и утратой Я.

Утверждение «Ядерное оружие это хорошо» иллюстрирует собой тоталитаризм факта, обладающий умерщвляющим эффектом для сознания. Бросается в глаза контраст между мягкими, нежными цветами, тонкими, воздушными контурами и ужасом главного посыла. Это – противопоставление жизни и смерти. Таким образом Пепперштейн решает очень важную задачу – защитить людей от натиска реальности, создать определенный зазор, люфт, барьер для несуществующего, дистанцию внутри нас самих, которая позволит не отождествляться бездумно и целиком с предлагаемыми точками зрения на поток событий, удушающе навязывающих нам самих себя. Выявление и фиксация сил и полей, которые определяют мышление, предоставляют возможность переопределить свое положение в их игре, не быть заложниками факта. Многомерность сознания, множественность миров и детская фантазия являются антидотами тоталитаризма.

То, что предлагается художником есть не эскапизм, но мечта и человечность, которые единственные способны сохранить сознание в схватке со смертью.

- «Правительства уверяют народы, что они находятся в опасности от нападения других народов и от внутренних врагов и что единственное средство спасения от этой опасности состоит в рабском повиновении народов правительствам. Так это с полной очевидностью видно во время революций и диктатур и так это происходит всегда и везде, где есть власть. Всякое правительство объясняет свое существование и оправдывает все свои насилия тем, что если бы его не било, то было бы хуже. Уверив народы, что они в опасности, правительства подчиняют себе их. Когда же народы подчинятся правительствам, правительства эти заставляют народы нападать на другие народы. И, таким образом, для народов подтверждаются уверения правительств об опасности от нападения со стороны других народов».

Фрагмент статьи Л.Н. Толстова «Христианство и патриотизм», написанной в 1893 году, но не опубликованной из-за цензуры, в которой производится тщательный анализ и критика феномена патриотизма, поставленного на службу власти и ведущего народ на верную гибель. Написанная после заключения франко-русского союза 1893 года как реакция на волну празднеств поднявшихся в обществе, статья выражает прежде всего возмущение глупостью народа, не чувствующего фальши в происходящем, но наивно ему радующегося.

Тонкий психолог как на уровне личности так и на уровне социума, Толстой развенчивает патриотизм как главную идеологию диктатур, к которой прибегают с целью манипуляции народным сознанием. Можно сказать что обличается именно тот патриотизм, который разделяет нации и людей, сеет раздор между народами, который под личиной идеала нравственности оказывается оправданием насилия. И в конечном счете выигрывают правители, заставляя людей выполнять за них грязную работу. Когда любовь к одному государству оборачивается ущербом другому, любовь становится ненавистью.

- Культовый фильм-апокалипсис Элема Климова – безжалостная по отношению к зрителю военная драма, вышедшая в кинопрокат в 1985 году к сорокалетию Великой Отечественной войны. Снятая в период «холодной войны» на волне страха перед Третьей Мировой, картина представляет из себя воплощение чудовищных военных кошмаров и считается одним из самых тяжелых к просмотру фильмов того времени. Ее действие происходит в 1943 году в Белоруссии, где в рамках утвержденного нацистской Германией «Генерального плана Ост» армия Вермахта проводит карательные операции с целью тотальной зачистки гражданского населения. Сюжет выстроен вокруг мальчика по имени Флера, который, проходя через испытания военного времени, претерпевает необратимые психологические изменения, непосредственно отражающиеся на его лице – из ребенка он становится стариком. Смерть близких, попытки самоубийства, угроза сожжения заживо, вынужденное присутствие при массовой казни и постоянное наблюдение за сценами насилия над соотечественниками – вот только некоторые из кругов ада, которые зритель проходит вместе с Флерой. Фильм наполнен красочными символами-метафорами противостояния жизни и смерти: танец под дождем и цапля выходящая из леса против агонии коровы и вьющихся над детскими игрушками мух.

Отбор актеров на главную роль происходил по особому режиссерскому регламенту: Климов показывал претенденту на роль хронику из концлагерей, а потом предлагал чай с тортом, ожидая человека, который откажется. Алексей Кравченко оказался единственным отказавшимся и получил роль. К нему были приставлены психологи и разработана специальная программа психологической помощи, которая позволила актеру сохранить здоровье после съемок.

Есть такая русская пословица «кто старое помянет, тому глаз вон, а кто забудет – тому оба долой». Она не о наказании за забывчивость, а о том, что нет ничего опаснее забвения. Климов предпочел сохранить хотя бы один глаз и навсегда оставить след в памяти коллективного бессознательного. Всякий хотя бы раз посмотревший этот фильм, можно сказать получает прививку от любых попыток романтизации хода военных действий и утверждается в понимании того, что на войне есть только проигравшие.

On the wave of the world’s doubts about the position of russian art in relation to militarism discourse, it is worth emphasize the fact that it is quiet difficult to hold a line of demarcation between poetic and political. If the poet of certain era chants a war – does this mean that he or she has to be excluded from cultural heritage? And vice versa – is anti-war rhetoric really able to save humanity from conflicts and catastrophes? More directly and openly the sense is manifested, farther it is from poetic, because the truth is multifaceted, mysterious and does not tolerate the interrogation mode. The poetic talent is correlated with the civil position of the author but not completely dependent from it. Attempts to reduce one to another are always in the risk to collapse into the conjuncture. Nevertheless, in the Russian artistic field we find a rich tradition of artists fully aware about horrific side of the war, far away from calming illusions and not afraid to face up the fact of its absurdity and terror. Understanding of uncovered brutality of warfare is the only way not to loose humanism and values that make life so precious. And on the contrary paranoia turns out to be the opposite side of self-deception.

- One of the faces of Moscow conceptualism, the creator of schizoid and fantasy worlds, Pavel Pepperstein, presented in 2014 a series of works called “Holy Politics”, among which of particular relevance stands the painting with a provocative title “The Internet is bad, and nuclear weapons are good». 2014 is the year of the culmination of european crisis, catastrophic and apocalyptic nature of which was understood by the artist and the consequences of which we all, the inhabitants of the earth, feel at this moment.

According to Pepperstein, the Internet and the networked-thinking that it generates are not less, and perhaps even more dangerous, than “zombie” TV – reference to a popular nowaday topic of fake news. One channel of propaganda is not much different from another, both form the illusion of community and belonging to something bigger than individual, toxic to consciousness. Identification of oneself with one or another information flow threatens with mental instability and loss of Self.

The statement “Nuclear weapons are good” illustrates the totalitarianism of the fact that has a deadening effect on consciousness. What we face looking at the painting is the opposition of soft, delicate, airy colours with thin contours to the horror of the main message. This represents the opposition of life and death. In this way Pepperstein resolves very important issue – protect people from the onslaught of reality by creating a certain gap for the non-existent, a barrier and distance within ourselves that will allow not to be identified immediately, completely and thoughtlessly with the proposed points of view on events that suffocatingly offer themselves to us. Revealing and fixing the forces and fields that determine thinking provide an opportunity to redefine one’s position in their game, in order not to be prisoners of the fact. Multidimensionality of consciousness, multiplicity of worlds and childish fantasy are the antidotes of totalitarism.

What the artist proposes is not escapism, but a dream and humanism, which are the only ones capable of retaining consciousness in the fight against death.

- «Governments assure nations that they are in danger from attack by other nations or from internal enemies, and that the only way of salvation from this danger lies in the slavish obedience of nations to governments. This is clearly seen during revolutions and dictatorships, and this is how it happens always and wherever power is at stake. Every government explains its existence and justifies all its violence by saying that if people had not been beaten, it would have been worse. Having assured the nations that they are in danger, the governments subdue them. When nations submit to governments, these governments force people to attack others. And thus, for these nations, the assurances of governments about the danger from attack from other nations are confirmed».

This is a fragment from an article by L.N. Tolstoy “Christianity and Patriotism”, written by him in 1893, but not published due to censorship. In this article he carries out a thorough analysis and criticism of the phenomenon of patriotism that is put at the service of power and that leads the people to spiritual and physical death. Written after the conclusion of the Franco-Russian alliance of 1893 as a reaction to a wave of festivities that arose in society, the article expresses, first of all, indignation against obscurity and naivety of the public that is not able to understand the falsity of superficial joy, but enchanted and ready to celebrate everything that is happening.

A subtle psychologist both at the level of the individuality and at the level of society, Tolstoy debunks patriotism as the main ideological ploy of dictatorships, which is invoked in order to manipulate the people’s consciousness. Tolstoy denounces such patriotism that divides nations and people, sows discord among people, and that, under the guise of an ideal of morality, turns out to be a justification for violence. With the help of such patriotism who really benefits are the political rulers, those that for the sake of their own interests, force a lot of fooled, simple-hearted and embittered people to shed their own and other people’s blood. When love for one state turns into damage to another, love becomes destructive force, it becomes hate.

- A cult apocalyptic film «Come and see» directed by Elem Klimov – a war drama merciless for a viewer, released in 1985 on the fortieth anniversary of the Second World war. Filmed during the Cold War period in the wake of the fear of the Third World War, the picture is the embodiment of war nightmares and is considered as almost the hardest film to watch. Its action takes place in 1943 in Belarus, where, as part of the «General plan Ost» adopted by nazi Germany army of Wehrmacht carries out punitive operations with the goal of total «cleaning» of the civilian population. The plot is built around a boy named Flyora, who, going through the trials of wartime, undergoes irreversible psychological changes that are directly reflected on his face – from a child he becomes an old man. The death of the family, suicide attempts, the danger of being burned alive, forced presence at a mass execution and constant watching of scenes of violence against compatriots – these are just a few of hell-circles that the viewer goes through with Flyora. The film is full of colorful symbols-metaphors of opposition between life and death: a dance in the rain and a heron emerging from the forest against the agony of a dying cow and flies hovering over children’s toys.

The selection of actors for the main role took place according to a special scenario: Klimov showed to the applicant for the role a chronicle from concentration camps, and then offered tea with cake, waiting for a person who would refuse. Alexey Kravchenko was the only one who refused and so he got the role. Psychologists were assigned to him and a special program of psychological assistance was developed, which allowed the actor to maintain his mental health during the process of filming.

There is such a Russian proverb «dwell on the past and loose an eye; forget the past and loose both eyes». It is not about punishment for forgetfulness, but rather about the fact that there is nothing more dangerous than oblivion. Klimov preferred to keep at least one eye and forever leave a mark in the memory of collective unconscious. Anyone who has ever seen this movie, gets vaccinated from any attempts to romanticise the course of hostilities and is affirmed in the understanding that in a war you may only loose.

Índice de ilustraciones:

Fig. 1: The Internet is bad, and nuclear weapons are good Pavel Pepperstein / Интернет это плохо, а ядерное оружие это хорошо Павел Пепперштейн

Fig. 2: L.N. Tolstoy in the family estate Yasnaya Polyana / Л.Н. Толстой в семейной усадьбе Ясная Поляна

Fig. 3: A shot from the film of E.Klimov Come and see / Кадр из фильма Э. Климова Иди и смотри